They say our ancestors were hunter gatherers that lived in isolated tribes, well blended within nature. They hunted animals and gathered wild edible plants for food and had evolved senses, similar to those of animals, being able to accurately read weather, hear far away sounds, see and interpret danger and plant edibility etc.

Ancestrally speaking we have evolved to move a lot, and have a mixed diet composed of wild plants and game. At least this is what happened for most of our history. Agriculture and the modern world changed that and it can be argued that we will slowly adapt to these more recent changes and incorporate them into our genetic build-up. However, this process will be slow if anything, and our hunter gatherer formatting will still predominate for the foreseeable future.

Why is this relevant? Because in order to achieve maximum health and longevity, we should try to emulate the hunter gather lifestyle as much as possible. At least as long as it doesn’t become socially weird. Nutritionally, our ancestors alternated between states of fasting and feasting: they fasted until they were able to hunt down specific animals and gather specific wild plants. Of course they must have tried to build regularity into their hunting & gathering schedules, but certainly the outcomes of those activities were not as exact as our current fixed meal & snack times. Which is also why a bit of stress variety can help.

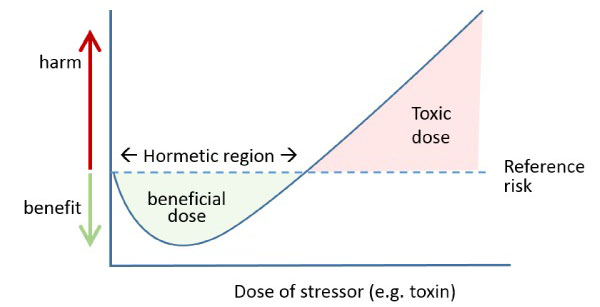

The overall concept of hormesis is the more big picture theme behind this adaptation. As with fasting-feasting cycles, when one doesn’t eat for a while and then eats again to his/her heart content, exposing one’s body to small stressors helps it become more resilient in general. Whether, it’s hot or cold, lack of oxygen or plenty of oxygen, physical activity or rest, fasting or feasting, the body’s biochemical processes are forced to adapt to different external environmental states. And this makes the body more adept at functioning in a variety of circumstances. As long as the stressors generated by these states are at appropriate levels for that specific body: not too small, so that there is no stimulation, but also not too big so that there is a risk of the body’s breaking down as it cannot adapt to a change in circumstantial conditions that is too big.

Diet composition falls into the same category: eating a diversity of foods forces the body to adapt to a variety of molecules to each food type, be them alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenes, phytosterols, stylbenes etc. The fact is that each food comes with its own genetic make-up and the human-food interaction teaches the human body to respond to a specific substance. And again, why is this good? Because the more substances the body is familiar to and can assimilate, the wider the biochemical flexibility of that body. And this gives resilience and adaptiveness.

And just to get a sense of how our diets have evolved over time, from the approximately 50000 edible plants in nature, it is thought that our ancestors used to have about 100+ consistently in their diets. What about us? Well, the most 15 cultivated plants constitute 90% of human diet these days, while the top 3 constitute about 1/3. And while an argument can be made that eating the same thing over and over again can also have positive consequences as the body becomes more familiar with breaking down that specific food, this can both upregulate certain biochemical pathways and exhaust specific enzyme reserves. This in turn creates imbalances in the body, which can malfunction as a result with repeated exposure to the same dietary stimulus.

So, bottom line, in this modern jungle our ours, you have to envision yourself as a modern hunter gatherer, hunting for (as gathering can have a slightly negative local connotation) an as big variety of foods as possible, while paying particular attention to the sourcing of those foods. This is what we do at NutriFix, where we aim to buy high quality ingredients to create meals consisting of diverse nutrients that vary from one meal to another!

~Mihai

| fixing nutrition

| fixing nutrition | based on genetics

| based on genetics | for enhanced performance

| for enhanced performance | and increased longevity

| and increased longevity